Some people recover quickly from cuts, muscle soreness, or minor injuries.

Others rest, eat well, and follow healthy routines, yet their wounds linger, stiffness persists, and recovery feels incomplete.

If you’ve asked yourself, “Why does my body heal slowly even when I rest?” the answer is often biological, not behavioral.

Research suggests that slow healing is frequently linked to how the body regulates inflammation, stress hormones, blood flow, and cellular repair, not simply how much rest or supplementation someone gets.

What “Slow Healing” Means, and Why the Body’s Repair Process Can Stall

In clinical and research contexts, slow healing refers to delayed or impaired tissue repair relative to expected healing timelines.

This can apply to:

- Slow healing cuts or wounds

- Prolonged muscle soreness or strains

- Lingering post-surgical recovery

- Recurrent injuries that fail to fully resolve

Healing is a coordinated biological process involving immune cells, connective tissue signaling, and adequate circulation. When these systems are dysregulated, repair may be delayed even in otherwise healthy individuals.

To understand why healing can slow or stall, it helps to look at how tissue repair normally progresses through distinct biological stages.

The Stages of Wound Healing, and Why They Can Stall

Research describes four overlapping stages of wound healing:

1. Hemostasis (Immediate)

Blood clotting prevents further bleeding and forms the structural base for repair.

2. Inflammation (Days 1–4)

Immune cells remove debris and pathogens.

Prolonged or excessive inflammation is strongly associated with delayed healing.

3. Proliferation (Days 4–21)

New blood vessels form, fibroblasts produce collagen, and cells migrate to repair tissue.

4. Remodeling (Weeks to Months)

Tissue strengthens and regains function.

Many cases of slow healing cuts or lingering injuries occur when the body remains stuck in the inflammatory phase or cannot effectively transition into proliferation and remodeling.

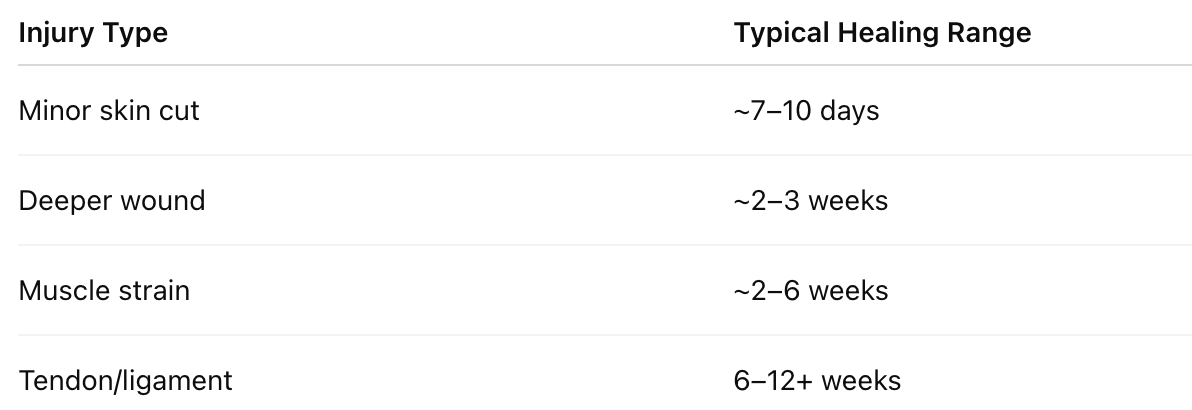

How Long Does a Cut Take to Heal?

Healing time depends on tissue type, circulation, immune status, and stress load.

Consistently exceeding these ranges may indicate impaired repair signaling, rather than normal variability. In research contexts, impaired repair signaling refers to disruptions in immune communication, cellular migration, and blood flow that are required for tissue repair.

Signs of a Healing Wound vs. Delayed Healing

Clinicians and researchers do not assess healing based on time alone. Instead, they evaluate patterns of change, whether inflammation resolves as expected, whether tissue remodeling progresses, and whether function gradually returns.

Research suggests that effective healing follows a predictable biological trajectory, while slow healing often reflects disruption at one or more stages of repair.

Common Signs of Normal Healing Progression

In uncomplicated healing, the body moves from inflammation toward tissue rebuilding and remodeling. Studies indicate the following signs are consistent with this transition:

- Reduced redness and swelling

Early inflammation is expected, but research shows that as immune signaling stabilizes, inflammatory markers decrease and visible swelling subsides. This typically reflects appropriate resolution of the inflammatory phase. - Gradual pain reduction

Pain often decreases as inflammatory mediators decline and tissue integrity improves. Persistent or worsening pain, by contrast, may suggest prolonged inflammation or delayed tissue repair. - Tissue closure or scab formation

During the proliferative phase, keratinocytes and fibroblasts migrate to close the wound surface. Scab formation or visible tissue closure is considered a normal sign of structural repair. - Improving mobility or strength

As collagen fibers reorganize and tissue regains tensile strength, functional improvements are commonly observed. Research links this phase to remodeling processes that can continue for weeks or months.

Together, these signs indicate that the body is successfully progressing through the stages of wound healing, rather than remaining stalled in early repair.

Signs Associated With Slow or Delayed Healing

When healing does not follow this expected trajectory, researchers often observe indicators of impaired repair signaling or unresolved inflammation:

- Persistent inflammation or tenderness

Studies suggest that chronic or dysregulated inflammation may prevent progression into the proliferative phase, delaying tissue reconstruction and prolonging pain. - Stalled improvement over weeks

A lack of measurable progress, even with adequate rest may reflect insufficient cellular migration, reduced fibroblast activity, or impaired blood flow to the affected area. - Recurrent reopening or irritation

Incomplete epithelialization or weak collagen formation can cause wounds to reopen or remain fragile, particularly under minimal stress or movement. - Ongoing stiffness despite rest

Research links prolonged stiffness to delayed remodeling and altered connective tissue organization, which may occur when repair processes are repeatedly interrupted or under-resourced.

Importantly, these signs do not necessarily indicate severe pathology, but they may signal that the body’s repair environment is compromised, rather than simply needing more time.

Why These Signs Matter Clinically

In clinical practice, these patterns are used to distinguish between normal recovery variation and delayed or impaired tissue repair. Healing is not a passive process. It requires:

- Controlled inflammation

- Adequate circulation and oxygen delivery

- Coordinated cellular signaling

- Sufficient metabolic and recovery resources

When these elements are disrupted, by chronic stress, repeated overload, or systemic inflammation, wounds and injuries may heal slowly even in otherwise healthy individuals.

Recognizing these patterns helps explain why some people experience prolonged recovery despite rest, nutrition, and conventional care.

Can Stress Really Delay Healing?

Yes, and the mechanism is well-documented.

Research in psychoneuroimmunology suggests chronic stress alters immune regulation, affecting:

- Cortisol signaling

- Inflammatory cytokine balance

- Nitric oxide and blood flow

- Fibroblast and collagen activity

These changes may prolong inflammation and reduce tissue repair efficiency, explaining why recovery can feel slow even without obvious injury severity.

In this context, burnout is not just psychological, it can influence physical healing capacity.

For a deeper, research-focused discussion of peptide mechanisms, see: Peptides for Healing

Lifestyle Factors That May Contribute to Slow Healing

Does Drinking Alcohol Slow Healing After Surgery?

Research suggests alcohol consumption may:

- Impair immune response

- Reduce collagen synthesis

- Disrupt sleep and hormone regulation

These effects may increase infection risk and delay wound repair.

Do Anti-Inflammatories Slow Healing?

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can reduce pain, but studies indicate that excessive or prolonged use may blunt necessary inflammatory signaling, potentially slowing muscle and connective tissue remodeling.

How to Heal Wounds Faster Naturally, Supporting the Repair Environment

Evidence-based strategies focus on supporting physiological conditions for healing, rather than forcing recovery:

- Adequate protein and micronutrients (e.g., zinc, vitamin C)

- Sufficient sleep and circadian rhythm alignment

- Stress regulation and nervous system recovery

- Gentle movement to promote circulation

- Avoiding repeated overload during recovery

For some individuals, particularly those with chronic stress exposure, repeated injuries, or recovery plateaus, lifestyle support alone may be insufficient.

When Recovery Plateaus: Clinician-Guided Support

When healing plateaus persist despite adequate rest, nutrition, and load management, clinicians may evaluate whether additional biological support is appropriate. In cases of persistent slow healing, clinician-guided approaches may be considered as part of a broader medical evaluation.

Programs offered by Nuri Clinic may include:

- A structured, 12-week clinician-guided protocol

- Peptides such as BPC-157 and TB-500, which research suggests:

- Have been studied for connective tissue signaling

- May support cellular migration involved in repair

- May influence blood flow regulation during recovery

- U.S.-compounded peptides

- Cold-packed delivery with medical oversight

These approaches are positioned as supportive, used under clinical guidance, and are not presented as cures or guaranteed solutions.

Learn how clinician-guided performance protocols are structured and evaluated at Nuri Clinic: https://www.nuriclinic.com/protocol/performance/study

Some bodies heal quickly. Others don’t, especially under chronic stress.

Slow healing is often associated with disrupted repair signaling, prolonged inflammation, and limited recovery resources.

Clinician-guided programs may help support recovery when lifestyle strategies alone are not enough.

Important Medical Context and Use Considerations

Consult a licensed clinician before beginning any medical protocol.

Peptides discussed are not FDA-approved.

This content is for educational purposes only and does not replace medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Individual responses vary.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Why does my body heal slowly even when I rest?

Rest is necessary for healing, but research suggests it is not sufficient on its own. Healing requires coordinated immune signaling, blood flow, cellular migration, and tissue remodeling. Chronic stress, unresolved inflammation, or impaired circulation may interfere with these processes, slowing recovery even when rest is adequate.

Can chronic stress really delay physical healing?

Yes. Research in psychoneuroimmunology suggests chronic psychological stress can alter cortisol regulation, immune cell signaling, and inflammatory balance. These changes may prolong the inflammatory phase of healing and reduce the body’s ability to transition into tissue repair and remodeling.

Does drinking alcohol slow healing after surgery or injury?

Research suggests alcohol consumption may impair immune function, reduce collagen synthesis, and interfere with sleep and hormonal regulation. These factors may contribute to delayed wound closure and increased infection risk, particularly during early recovery phases.

Do anti-inflammatories slow healing?

Anti-inflammatory medications can reduce pain and swelling, but studies suggest prolonged or excessive use may blunt necessary inflammatory signals involved in tissue repair. In some cases, this may delay muscle or connective tissue remodeling rather than accelerate recovery.

Is slow healing always a sign of a serious condition?

Not necessarily. Slow healing does not automatically indicate disease. Research suggests it may reflect temporary physiological strain, stress-related immune changes, or recovery resource limitations rather than underlying pathology.

When should someone seek medical advice for slow healing?

Persistent wounds, recurrent injuries, or lack of improvement over expected healing timelines may warrant clinical evaluation, particularly when accompanied by pain, inflammation, or functional limitation.

Research References:

- Guo, S., & DiPietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219–229.

- Gurtner, G. C., Werner, S., Barrandon, Y., & Longaker, M. T. (2008). Wound repair and regeneration. Nature, 453(7193), 314–321.

- Eming, S. A., Martin, P., & Tomic-Canic, M. (2014). Inflammation in wound repair: Molecular and cellular mechanisms. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 134(3), 514–525.

- Marucha, P. T., Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Favagehi, M. (1998). Mucosal wound healing is impaired by examination stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 60(3), 362–365.

- Glaser, R., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2005). Stress-induced immune dysfunction: Implications for health. Nature Reviews Immunology, 5(3), 243–251.

- Radek, K. A., Kovacs, E. J., Gallo, R. L., & DiPietro, L. A. (2008). Acute ethanol exposure disrupts VEGF receptor cell signaling in endothelial cells. American Journal of Physiology–Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 295(1), H174–H184.

- Marsolais, D., & Côté, C. H. (2001). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and skeletal muscle healing: A review. Muscle & Nerve, 24(10), 1316–1328.

- Chang, C.-H., Tsai, W.-C., Hsu, Y.-H., & Pang, J.-H. S. (2011). Pentadecapeptide BPC-157 enhances tendon fibroblast migration and survival. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 29(5), 766–772.

- Goldstein, A. L., & Hannappel, E. (2015). Thymosin beta-4: A pleiotropic peptide regulating wound healing and inflammation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1348(1), 62–69.